This interview was originally posted by James Pethokoukis for his newsletter ‘Faster, Please!’

The US hasn’t hosted a World’s Fair in decades, but the fairs are still happening in other countries. Why is it so important to bring them back to America?

World’s Fairs have a long and storied history in America, but few know how important they were in shaping our country.

In 1893, Chicago hosted a Fair that drew 27.5 million guests — nearly 40% of the U.S. population before there were cars, planes, or highways. Guests saw a city illuminated by electricity for the first time, marveled at the architecture that would inspire the City Beautiful movement, and rode the world’s first Ferris Wheel.

In the decades that followed, the American World’s Fairs continued to amaze guests from around the globe. They debuted the steam engine, the telephone, the Model T and its assembly line, broadcast television, and touchscreens accelerating their mainstream adoption. They are responsible for symbols of progress that stand to this day, like San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts and Seattle’s Space Needle. They spread the ideas of some of history’s most influential people like Walt Disney, Amelia Earhart, Booker T. Washington, and Albert Einstein. They inspired millions of American children, including Carl Sagan and Neil DeGrasse Tyson, to marvel at our universe and the cosmos.

The Fairs were a place that brought together people from all different backgrounds and created common ground to discuss our country and our future. Today, what we need now more than ever is to come together and have a conversation about a future worth building. By bringing the Fairs back to America, we can promote a collective vision for a better world — reminding us how connected we all are and how far we can go if only we go together.

How have World’s Fairs changed over the years and why does that matter?

Today, World’s Fairs have been rebranded as “International Expositions” that occur every 5 years. Over the past few decades, their focus and structure has shifted from a cohesive narrative about the future and industry to more of a showcase of individual nations. Each nation has the opportunity to creatively brand itself, share infrastructure projects, and promote their foreign investment opportunities. While this model serves its own important purpose, we’re now missing the cultural value that past Fairs brought: an exciting and hopeful narrative for what the future holds.

What work are you doing on this project, and how optimistic are you that the US will host a World’s Fair in the next decade or so?

My goal is to recapture the impact that the earlier Fairs had. To do so, it’s simply not enough to bring the current version of the Fairs to the US, or even to re-run the playbook that was successfully used for past Fairs. The world has changed — particularly the ways that information and ideas are shared – so the Fairs must be reimagined to meet the needs and challenges of our time.

To make this reimagining happen, I’ve brought together a small team to rethink every piece of the Fair. From the physical infrastructure to the integration of different technologies to the guest experience, we’re focused on telling an exciting and compelling story about our future that not only gives guests hope, but inspires them to be a part of building it.

There’s obviously a lot that needs to go right, beyond redesigning the Fair. We’ll need to partner with the right cities and work with stakeholders in every industry and in policy. But we’re cognizant of these needs, and we’re working on a timeline that has me quite optimistic that we’ll host a World’s Fair in the next decade or so. The faster the better.

Why are World’s Fairs still relevant in the digital age? Can’t we just do “exhibits” on YouTube or in the metaverse, especially since so many innovations today are in software?

In the planning of every World’s Fair, there were skeptics who insisted that the day of the Fairs was over. But time and again, this has been proven untrue. Expo 2020 in Dubai drew 24 million guests from around the world, and Shanghai in 2010 hosted 73 million. And if the past two years have taught us anything, it’s that humans crave real, in-person experiences, which is why we’re seeing so much enthusiasm for the return of music festivals, sports games, and theme parks. It speaks volumes that when given the opportunity to go fully digital, people overwhelmingly demanded the return of in-person experiences.

To be fair, past and even current models of the Fair, which did and do rely on exhibits, are losing relevance in the digital age. When it comes to pure information sharing, digital tools have an effectiveness and scale that in-person Fairs can’t compete with. But that’s why we’re doing things differently, and actually leveraging the advantages of the digital age to our benefit. We’re combining these technologies with in-person experiences to create a product that’s more than the sum of its parts. This will not only show up in the Fair’s physical design, but also in remotely-accessible versions of the Fair that can reach kids around the globe.

And this approach actually creates a lot of value for digital and software innovations. Even impactful software can often feel abstract, and removed from people’s lives. By providing real-world experiences where guests can see these innovations being applied, the Fair can connect people with technology and foster an understanding of how it improves their lives. With our model, guests will get a life experience that they share with their friends and family; where they taste things they’ve never tasted, touch things they’ve never touched, hear things they’ve never heard, and find themselves immersed in a story about a positive future that is enabled by technology.

What is the best-case long-term impact you envision for a US-hosted World’s Fair?

If done right, the World’s Fair can be the catalyst for us to translate the hopeful stories we tell about the future into the real world. For that to happen, people need to leave the Fair with renewed hope; they need a vision of where we’re going, paths to get there, and the belief that they have a role to play.

We’ve actually reimagined our Fair with this long-term impact as a primary goal. Without getting into too much detail, we have components of the Fair that are intentionally designed to not only show people what a beautiful and abundant future can look like, but also highlight the technologies and projects being done today that will enable that future.

No matter what people are most passionate about — whether it’s food, energy, transportation, space, climate, computing, cities, or something else — they’ll leave the Fair with a sense that the future is bright and that there are clear ways for them to participate in building it.

My hope is that in 2080, the people who have solved today’s most pressing problems will look back on the Fair as the moment they decided to act.

Where did your fascination with World’s Fairs and techno-optimistic futurism come from?

The techno-optimistic futurism first hit me when I was 10 years old during my first trip to Disneyland. I explored this discreet building in Tomorrowland called the Innovention Center Dream Home.

Inside this building, I found myself enamored by all of the technology: a talking kitchen, a 3D printer, an augmented reality mirror, ASIMO the little Honda robot, a piano that played itself, and touchscreens all over the walls. Mind you, this was in 2005 and I was coming from a small town north of Seattle, so I’d only seen things like this in movies. Being able to touch, feel, see, and ultimately experience these technologies in the real world showed me how incredible the future could be and inspired me to be a part of building it.

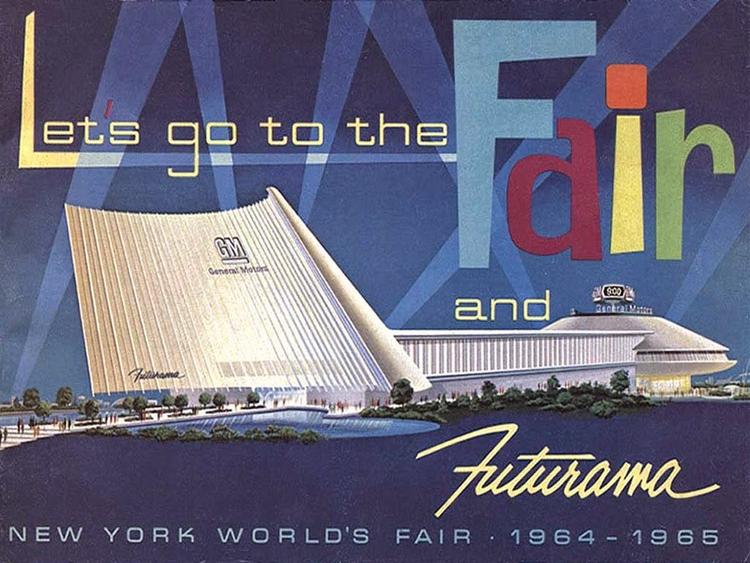

On the Fair side of things, I grew up outside of Seattle and have always loved the Space Needle — a remnant of the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair — so the Fairs were always on my radar. The fascination didn’t manifest, though, until I took a road trip early on in the pandemic. I was driving down the freeway, listening to the Walt Disney biography when it mentioned the work Walt was doing with the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Something clicked and I asked myself one simple question that changed everything: What happened to the World’s Fairs?

I’ve been obsessed since.

Is there a recent work in pop culture (film, TV show, video game, novel, etc.) that you would point to as an example of the abundance/pro-progress vision?

One of the few examples I can point to that gets close to this vision is Kim Stanley Robinson’s Ministry For The Future. Even though this book isn’t explicitly abundance driven, it does do a good job of providing an optimistic (though complicated) path toward a better future.

That said, this question highlights an important, but often overlooked problem: that we lack compelling stories that promote exciting, abundant, and pro-progress visions of the future. This matters because the stories we tell about the future deeply influence how we view it and what we build.